Turn on English subtitles of the YouTube video.

Turn on English subtitles of the YouTube video.

What promises to be the end of Bogotá, the southern edge of the city, is a mix of mountains upholstered with grass and rock, and others on which uneven brick houses rise. Facing this landscape, in the upper part of Potosí, a neighborhood in the locality of Ciudad Bolívar [i], eight children and three young people spot two antagonistic mountains: the mountain of Palo del Ahorcado —whose name comes from an old eucalyptus that stands alone at the top—, and another on which are the humble houses that draw the Caracolí neighborhood in the same locality.

This “other city”, as the writer Arturo Alape named it in the book Ciudad Bolívar: la Hoguera de las Ilusiones, extends towards the ocher of the mountain and folds between facades painted in yellow, green and aquamarine blue, which make up mediocre the inequality and poverty that exist there. That is palpable in the illiteracy rates, informal work, overcrowding and difficulty in accessing public services.

It is Saturday. 8th of June of 2019, and the atmosphere is filled with the screams and sincere laughter of the eight children who gaze with enthusiasm at the landscape they already know. Suddenly, a loud voice catches his attention. It is Juan Ortega, a student of the Bachelor of Mathematics at the National Pedagogical University (UPN). Juan has a square jaw and a piercing in his left ear. He wears a long-sleeved blue T-shirt, with the “64” on the back, the name “Juanito” and the title “Gestores de Paz”.

Along with him, his colleagues Luisa Tabares —brunette and with a broad laugh— and Nedzib Sastoque —long hair at shoulder height and a black backpack strapped to the shoulder — write what is happening. All pending that no child falls.

Juan speaks to them like a teacher, with the desire of who he wants to teach; and children try to follow him, wanting to learn. It seems that he has been doing this for years, that the trade has hardened him, but he is only 19 years old.

The entire team of leaders call themselves mentors of Gestores de Paz(Peace Managers), a social work with children and young people from the Potosí neighborhood. The leadership began with the NGO World Vision, but which in recent years has been sustained by the will of a group large number of local youth.

—Matías, how do you feel when you look over there? —Juan asks the group of children, pointing to the landscape of southern Bogotá.

—I feel like I'm swimming in a pool.

—Dylan?

—Fear.

—You?

—Peace.

—And you?

—Sadness.

What Juan, Luisa and Nedzib feel is a mystery, because the only thing that seems to worry that group of leaders are the emotions of the eight children who accompany them. Added to the conviction that they are valuable, that everyone has the right to live well .

Attached to the scene are the cautious glances of strange people passing by, the cantina music and the ‘guaracha’ that flood the atmosphere, and the irascible cold of that mountain in Ciudad Bolívar.

Being young in the locality of Usme, Bosa or Ciudad Bolívar, the Bogotá’s south, means fighting to survive. Before starting the new century, Alape warned: the youth of "the other city" is in danger. And it is because death is partying all around the streets of Bogotá, as it has been for years throughout the national territory.

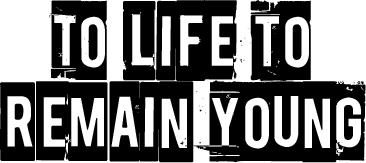

Usme, Bosa, Kennedy and Ciudad Bolívar accumulate almost half of all the murders registered in Bogotá in 2019 (511 of 1047 murders), by the Directorate of Criminal Investigation and Interpol (DIJIN), and a few over half of all murders of young people during the same year in the capital city (213 of 420 young people murdered).

Since 2018 we have traveled to Bosa, Usme and Ciudad Bolívar, looking among their young people for those who will bet on the defense of Human Rights. Furthermore, we wonder if these young people had guarantees to do so, and if to be believing in a life at the service of their community they were taking any risk.

Being a leader or a youth social leader in the periphery is, in addition to surviving, a commitment to building a possible city for the people and the territory of the Bogotá on the margins. Alejandro León was the first leader we interviewed in September 2018. Today he is 24 years old and is about to graduate from the Bachelor of Social Sciences at the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. With his gray beret, his bomber jacket and a small expansion in the left ear he talks about his "change proposal"; the ideal that makes him work so that the children of the Manzanares neighborhood, in the locality of Bosa, adjacent to Ciudad Bolívar, through football the children do not feel alone. “It is a different recreational space for children and young people. It is like an agent of change. They see school —the social leadership— as something different that reaches a neighborhood where nothing has come”, he explains.

Jhon Fredy Moreno is 25 years old, with eyes the size of pistachios and a beard that darkens his chin. His ears have two expansions the size of blueberries. He wears a brown ruana that fits custom him. As he turns his back on the mountains full of houses that can be seen from his rooftop, in the Monteblanco neighborhood of the locality of Usme, he says that not everyone likes to work for the well-being of the communities in neighborhoods that need it. The reason why El Escenario, his cultural house, has experienced risky situations.

“We have had difficulties. In the second year —2016— they broke our windows, graffitied the house because there were some students who were stopping doing some jobs or some... errands —microtraffic— to come here”, Jhon recalls.

Darling Molina is part of Gestores de Paz, and from the mountain in Potosí she is aware of how uncomfortable her leadership can be. Despite this, with the other young social leaders of Gestores de Paz, she never tires of claiming what she considers his community deserves. She has strength and eloquence in the word. Under the guise of a simple conversation there is a solid discourse, consolidated from the experience of actively inhabiting the south of the capital city of Colombia. What she has built with her community led her to study social work. She is 22 years old, has dark eyes, her hair shaved on the right side and wears a nose ring.

“That the lives of the young people upstairs be guaranteed —Potosí neighborhood—, not only up above, but in the locality —Ciudad Bolívar—. That there is access to opportunities, that there is a guarantee of minimum services, that it does not make the 'pelaos' (the children) have to 'rebuscársela' (survive) whatever it is and that the 'pelaos' do not make the only thing they think in their life is 'levantar lukas' (get money) whatever as it is, because that is 'what there is no' and 'is what we need'. That they can actually contemplate being part of any other type of scenario, that they can be in the locality, that they are transformative, that help to build a different city, ”says Darling.

Consequently, every weekend she and the other mentors from Gestores de Paz work in the Potosí neighborhood; or at least it was before the COVID-19 pandemic set in in the city. With the quarantine, the problems of her communities have worsened and the leaderships have been conditioned and forced to reinvent themselves.

Arturo Alape invites us to rediscover, amid daily life, violence and resistance, the “other city”. And definitely from the social leaderships of the youth of the periphery those concepts tell another Bogotá.

After the signing of the peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), in November 2016, the assassination of social leaders in Colombia increased and, consequently, the issue became relevant on the agenda of social organizations, also impacting the public agenda.

The president of the Patriotic Union (UP) and senator for the Decentes party, Aída Avella, does not hesitate to affirm that the murder of social leaders at the national level responds to a systematic plan, just as it happened with the UP genocide, a party formed at the end of the eighties by demobilized guerrillas from different organizations.

However, the studies that seek to explain what happens with the persecution of leaders, the journalistic works that analyze and narrate the murders of leaders, and the organizations that try to keep the data and make the problem visible have focused on rural areas - where the ravages of the armed conflict and the consequences of poor compliance with the Peace Agreement have made it necessary to report the perpetuation of violence against those who defend human rights—, leaving behind the leadership processes that take place in the cities

One of the organizations that has made the problem of social leaders in Colombia more visible is Somos Defensores, which seeks to “develop a comprehensive proposal to prevent attacks and protect the lives of people who are at risk for their work as human rights defenders, when safeguard the interests of social groups and communities affected by violence in Colombia ”, as read on their website.

Sirley Muñoz, communications and information system coordinator for the organization, explains that the capital city has its own dynamics. Sitting on the 13th floor of an office in the center of Bogotá, from which the south of the city is observed, she recognizes that little is known about the social leaders of the capital city. “The information systems that monitor violence against defenders and leaders have a very large gap in monitoring attacks by leaders and defenders in the capital city, because we have perceived Bogotá as a receiving city - of leaders displaced from the country's territories. in conflict-. I think that being so much the center we are erased from the panorama ”, she points out.

She is emphatic in stating that due to the diversity of movements and social organizations that the capital city has, more attention should be focused on the dynamics and risks of the city

So ignoring the dynamics of social leadership in Bogotá is not even having the youth in the picture. Even the information systems of public institutions lack data on youth leadership.

Unknowing the youth leaderships that are solidifying in the southern edge of Bogotá, gives clues about the state's indifference towards a part of the capital city that supports deep and systematic socioeconomic conflicts.

Turn on English subtitles of the YouTube video.

Bogotá is a vertical city. From its geography, along the Eastern Cordillera, the capital city is shown as a line in which inequality grows progressively from north to south, until culminating in the marginality of the edges where its inhabitants do not enjoy the quality of life from the other end of the city. While on Calle 57 A sur # 30 (at the south of the city) there are uncovered streets and zinc sheets used as house doors, on Calle 57 A # 30, on Avenida NQS (at the north of the city), which connects the south with the north, is the Movistar Arena, a center of shows whose construction required an investment of $ 70,000 million pesos (US $ 25.8 million).

According to the 2017 Multipurpose Survey carried out by the District Secretary Planning of the Mayor's Office of Bogotá, the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) and the Government of Cundinamarca, "most multidimensional poverty accumulates at the south of the city".

This data is confirmed by the cartographies of socioeconomic stratification by location of the District Secretary Planning, used to collect public services with differential rates and to assign subsidies and contributions to households. In them, it can be seen that Ciudad Bolívar, Usme and Bosa are part of the southern localities with the greatest presence of ‘estratos’ 1 and 2.

Added to the poverty rates of these localities in Bogotá is the impact of an armed conflict of more than 50 years. From multiple parts of the country, victims of the war have sought to cheat death by hiding and trying to rebuild their lives in the southern suburbs.

According to the April 9, 2020 Report of the Observatorio Distrital de Víctimas del Conflicto Armado, of 340,376 victims recognized before the Sole Registry of Victims (RUV) who live in Bogotá, 236,502 have their place of residence in Bogotá (SIVIC) characterized.

The five localities with the highest concentration of victims of the armed conflict and who reside in Bogotá are: Ciudad Bolívar with 38,859 victims, Bosa with 35,441 victims, Kennedy with 30,252 victims, Suba with 21,806 victims and Usme with 16,246 victims.

Despite the social conditions, in Ciudad Bolívar, Usme and Bosa, youth leaders emerge to fight for a dignified life in their communities. However, the guarantees for them are questionable.

According to Francisco Pulido, Director of Human Rights (2017-2019) and Undersecretary of Governance and Guarantee of Rights (2017-2020) of the Secretary of Government Bogotá, the highest number of threats and indexes of risk and vulnerability situations reported by the Social leaders are in “Ciudad Bolívar, Bosa, Usme, Rafael Uribe Uribe”.

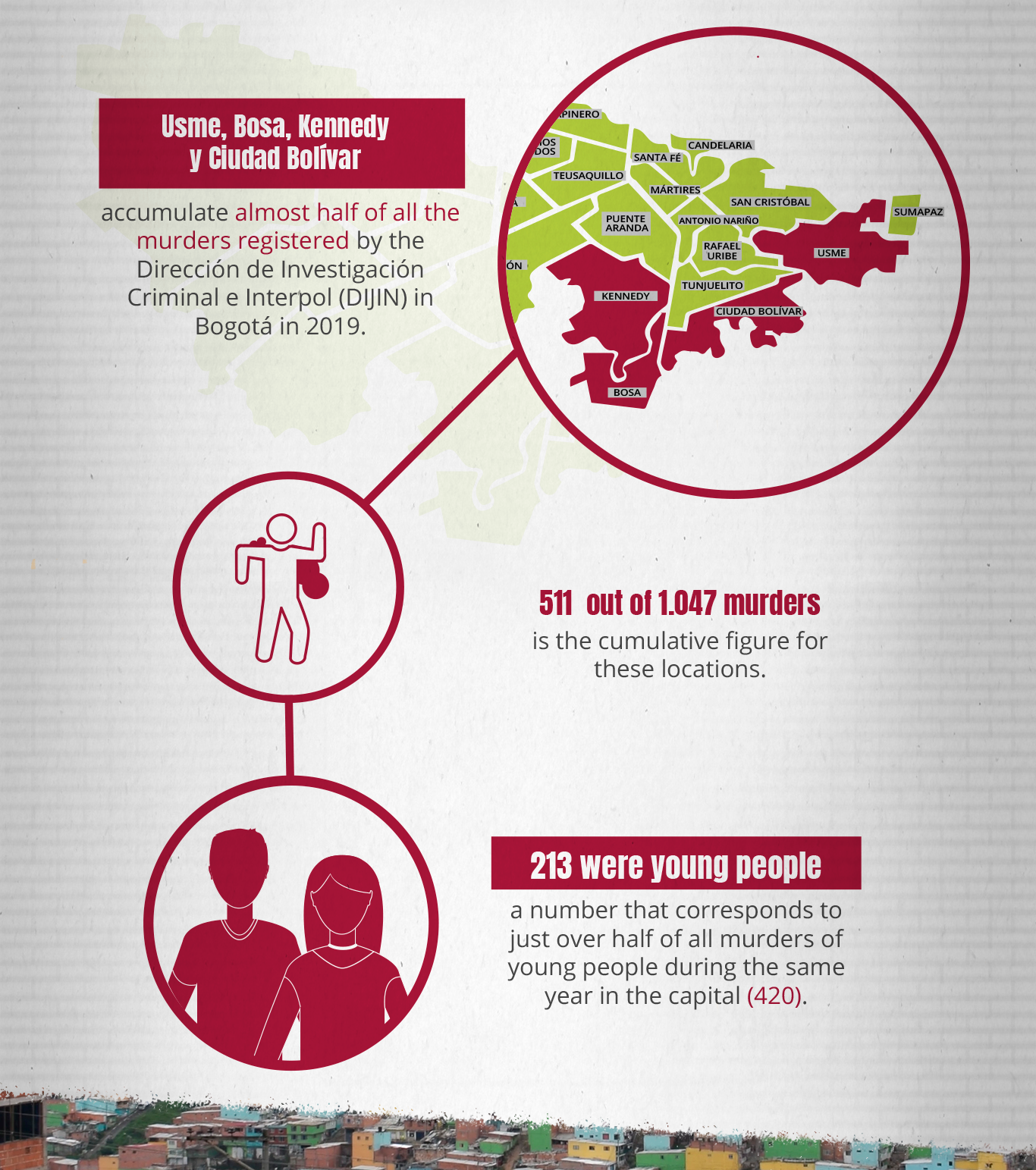

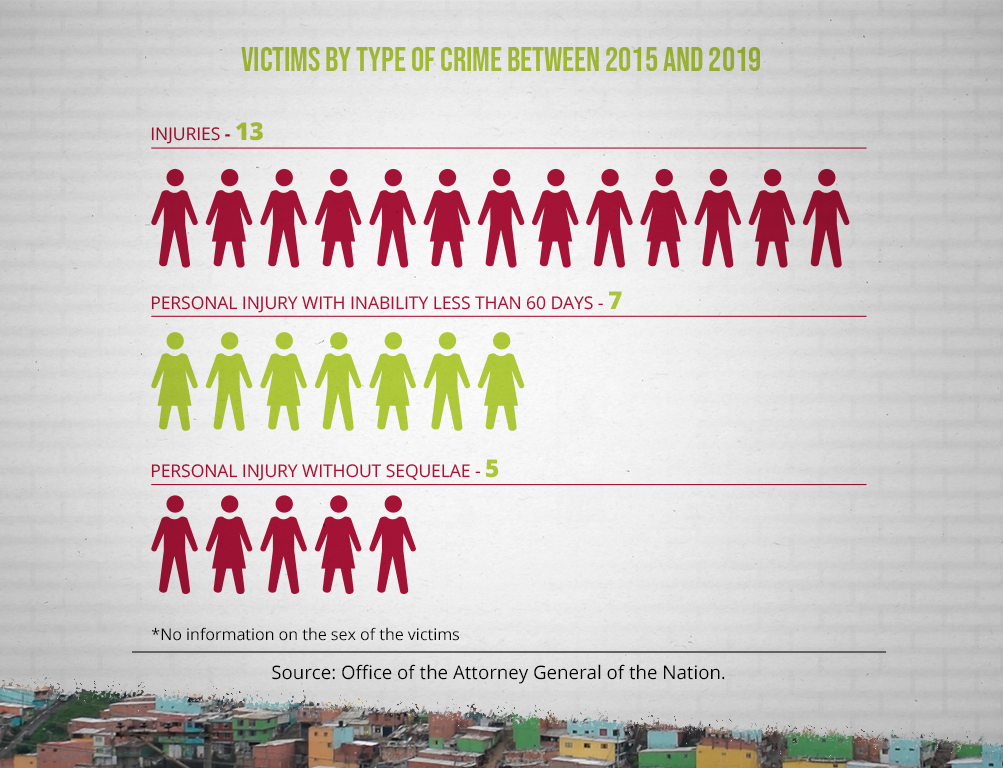

The Office of the Attorney General of the Nation recognizes, through the response to a right to petition, the existence of a sub-registry of data on homicides and injuries against social leaders in Bogotá. It indicates that: “it is important to take into account that (the data they provide) present a certain level of underreporting with respect to variables related to the characterization of the profiles of victims and indictees. This is due to gaps or little precision of this type of information at the time of receiving the complaints or throughout the advance of the criminal process.

In the cases reported by the Prosecutor's Office, it is impossible to know who are young people, because the investigating entity protects this type of data. However, the consolidated ones leave between seeing some dynamics of violence against social leaders in the capital city.

On the other hand, of the five follow-up notes and five early warnings issued by the Ombudsman's Office, which warn of risk situations in Bogotá, eight show the risk of human rights defenders, social leaders and children, adolescents and young people. These documents warn of the vulnerability for the defense of human rights, the presence of alleged Organized Armed Groups (GAO) and the possible recruitment of boys, girls and young people by criminal gangs or micro-trafficking.

Five of the documents mentioned specifically mention the localities of Ciudad Bolívar, Bosa, San Cristóbal, Usme and Rafael Uribe Uribe. However, none of these evaluations speak of the danger that young people who lead social leadership may be running.

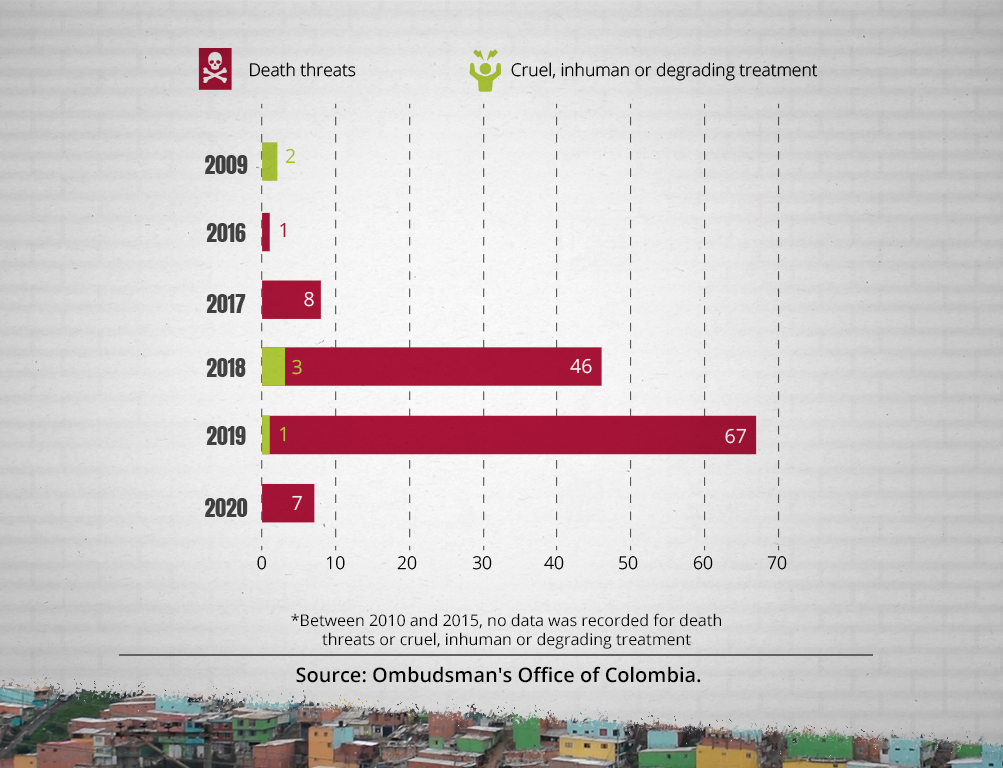

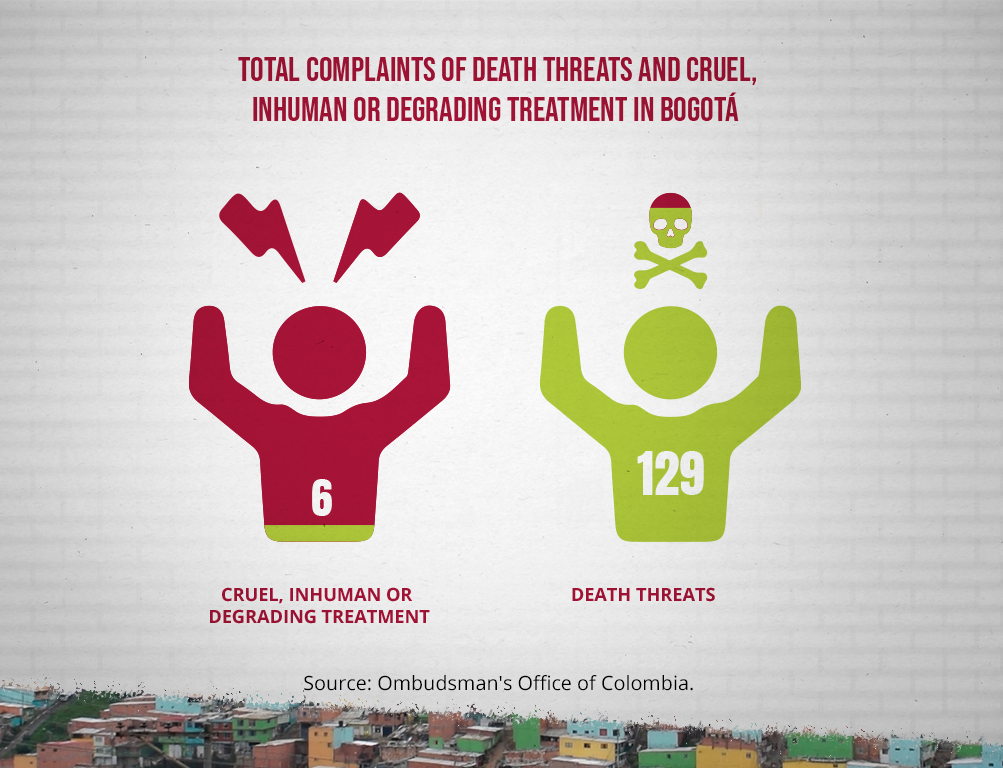

The VisionWeb Institutional Information System of the Ombudsman's Office registers, from 2009 to February 18, 2020, 135 violations of the rights to life and integrity, due to threats and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, whose affected are part of the group social leaders.

Until 2017 the record of death threats is low. However, the number rises in 2018, registering a total of 46 complaints, and in 2019 going to 67. However, the data shared by the institution does not include age, because according to Andrea Soler, a member of the National Directorate of Attention and Procedures for Complaints of the Ombudsman's Office, the information system does not allow this disaggregation.

In the same time range, the Early Alerts system records two murders of social leaders in Bogotá, one in the locality of Kennedy (2016) and the other in Usme (2017). None belong to the young age group.

When reviewing the annual reports of Somos Defensores, from 2010 to 2019, 23 murdered social leaders were found who were carrying out their work in the capital city. Of the 15 who were able to find their age, three were young: Alex Alejandro Benavídez Ayala (2012), Oscar Eduardo Sandino (2013) and Carlos Enrique Ruíz Escárraga (2014).

Alejandro Acosta, doctor in education and general director of the International Center for Education and Human Development Foundation (CINDE), a research center for innovative alternatives for human development and a dignified life for early childhood, childhood, adolescence and youth, ensures that young people are stigmatized as dangerous subjects for society, which is why they are frequently limited and excluded, depriving them of the possibility of fully exercising their right to be citizen. Therefore, to be young in Colombia is to face an established order that despises its music, its clothes and its ways of interacting on the street corners of the neighborhoods.

The opportunity to imagine a city from the youth has been co-opted, on a recurring basis, by an adult-centered perspective of a world that changes without respite and to which the Colombian State does not manage to respond to guarantee a dignified life for all its citizens, producing levels of inequality and high forms of exclusion. Young people are aware of this situation.

“In the case of the south, in Bogotá, it is showing that there are very beautiful experiences of a very different kind. I say beautiful both in the aesthetic sense, let's say phenomena like the entire graffiti movement, the entire music movement, of different expressions and in different artistic expressions, which come to build a different world for young people that allow them to resist and re-exist in these conditions in very positive ways. They are also combined with movements that seek to overcome social inequalities, forms of exclusion or other types of relationships such as the protection of the environment, ” says Acosta.

Senator Aída Avella believes in the vehemence of the Colombian youth. She assures that young people are reacting to the bad government, and that the social protests that took place in 2019 in the capital city are a reflection of the activism of young people and the intolerant position before a “mafia, thief and parasite elite”.

Turn on English subtitles of the YouTube video.

The director of CINDE acknowledges that one of the problems in terms of available information on youth incidence in social processes is the little study on children and youth throughout Latin America. “I believe that in the country we urgently need to give priority to building a serious, rigorous, systematic information base on youth, and we need to strengthen research. (...) We have to create a creative dialogue between the science and technology system, the educational system and the construction and operation of social policies and the relationship of the movements that are taking place at the level of the social base ”. This could be the way to identify the incidence of young people in social leadership in the country.

In Bogotá, according to the Information System of Social Organizations of the District Institute for Participation and Community Action (IDPAC), of the 2,432 social organizations characterized up to February 2020, there are 739 youth processes with 15,392 young members, that is, people who are between 14 and 28 years old, as dictated by the Juvenile Citizenship Statute. In addition, the locality of Ciudad Bolívar ranks first with 2,595 young members of social organizations.

Alejandro León is one of the young people who does not appear in the IDPAC bases. He grew up on the outskirts of the locality of San Cristóbal. “I grew up watching one of my best friends murdered, as a child, by a stray bullet. That's when I began to wonder why, why does this happen in the peripheries ”. The example of his father, also a social leader when he was young, added to the academic spaces, contributed to his early concern for social mobilization and community well-being.

“I joined a group of skinheads, it was called the Suba Antifascist Front. There we carried out different activities such as murals, such as ‘aguapaneladas’. We came to the center to distribute clothes and food to the homeless ”. With a left-wing political background, he found in soccer an exercise of communion that allowed him to start working with children on the outskirts of the city. The key was to teach through sport a different possibility of life.

“We use football to build ourselves as people and to build the identity of a neighborhood. And that's where Tigres del Sur was born first and then Lenin Killers ”, two popular soccer schools that Alejandro founded, the first in the Divino Niño neighborhood of Ciudad Bolívar; the second in the Manzanares neighborhood, in the locality of Bosa, also located in the south of the city. In January 2020 Lenin Killers changed his name to Seeds of Resistance.

Alejandro does not consider himself a social leader. He not in the strict sense of the word. It seems to be something frequent in the social leaderships of the youth of the capital city: they do not fully throw themselves into their leadership title, although they are indisputably so. Always aware of their communities, always combative, always fighting from the southern edge of Bogotá to make it a possible place.

Like Alejandro, María Fernanda Ríos and Gabriela Romero they work with the community of the locality of Bosa, through community theater at the Casa Raíz cultural house; they teach theater to children through a seedbed of their group Teatro del Sur.

Also Ánderson and Jhon Freddy work with the community in art houses in Usme. Likewise, the group of Peace Managers made up of: Nedzib, Lisa, Yhoyner, Darling, Nicoll, Valentina, Juan Carlos, Luisa, Cristian, Sindy and Suri, are committed to change from aesthetic expressions. All young. All working in places where the State has a historical debt. All unprotected and in danger. However, with the desire for a change for his generation.

In the description of the SoundCloud you can see the English transcription of each podcast.

Since 1998, the United Nations (UN), through the Declaration of human rights defenders, laid the foundations for the recognition of the figure of the human rights defender as the one or the one who undertakes the defense of these. In addition, it demanded that the States guarantee the execution of these processes and the protection of the lives of all those who work in them.

In Colombia, the figure of “social leader” is a concept linked to rural territories or municipalities other than departmental capital cities. Leonardo González, conflict and human rights coordinator at INDEPAZ, assures that "a social leader can be a grassroots person, as long as he defends human rights and is recognized by his community as an important person for the achievement of his objectives."

Sirley Muñoz, from Somos Defensores, is emphatic that the institution takes into account the persistence of the defense of human rights to conceive of a person as a social leader. Consequently, she affirms: “the social leader has a very strong process. A human rights defender can be anyone who wakes up any day and wants to defend a right, who sees that there is an injustice and begins to promote a cause. On the other hand, when one sees the leaders in the territory, the leaderships are deeply rooted, they are people who have worked for the community all their lives, they are people who have been on the community action board for many years. So there are some small differences, but all social leaders are human rights defenders”.

The Secretary of Government of Bogotá, explains the former official Francisco Pulido, aligns itself with the characterization of leaderships of the protection program of the Ministry of the Interior, within which the "youth and childhood leader" is recognized. The programs designed by the institution for the protection of social leaders are extended to all human rights defenders, considering the dimension of social leadership as an extremely broad category, which in the end includes a group of people who promote access to rights of a certain community.

“We, as a territorial entity, are the district administration, we have limited competence to the territorial boundaries of the district in the 20 localities. We of course know the national reality, there have been reports in reports since 2017 of more than 300 murdered social leaders. It is not official information from the Office of the Attorney General of the Nation, but we know the situation and its seriousness. For this reason, we built a protection route for social leaders in the district ”, said Pulido.

The then undersecretary for Governance and Guarantee of Rights of the Ministry of Government was emphatic that until May 8, 2019, the day of the interview, no leader had died who had accessed the District Route of Protection for Defenders and Human Rights Defenders, but she recognized that it was important to continue working on the routes to disseminate the route, so that more leaders knew about it.

Regarding the incidence of young people in social leadership processes, Pulido assured that participation mechanisms exist. “We have a district youth policy with important participation scenarios. But we also seek that youth leaders are not only participating in youth policy, but that they are participating in all decision-making instances that affect them. For example, we have a district human rights system, and we guarantee that with representatives the youth platforms have a seat there and participate with the right to speak and vote ”.

The policy that Pulido speaks of does not guarantee the leadership of young people or their interest in participating in official instances. The latter is due, in many cases, to the strong feeling of disarticulation that many social leaders feel with government policies and the same institutional figure.

Turn on English subtitles of the YouTube video.

It is Sunday, July 7, 2019. The Potosí neighborhood community enjoys life between soccer games, a community sancocho and bingo. Children come out from everywhere, wherever the gaze is fixed there are children who run, laugh and playfully hit different objects. Colors and sounds vibrate on every surface. The icy wind embraces everything and everyone in the place —even if the inhabitants of the edge of the city have the superpower to be indifferent to the cold—. Everyday life from the micro-soccer fields at the end of the hill shines: it is the birthday of the soccer school of Gestores de Paz.

The community, beyond the sancocho and football, celebrates the social leadership of this group of young people, who year after year, without seeking recognition, work to make a city possible for the inhabitants of Bogotá on the margins.

Young social leaders are part of the revelry without taking much prominence. Darling dances salsa, Juanito has a beer, and the other leaders play with the children. Everything that happens there is a reflection of building community.

Thus, young social leaders resist from the southern border of the city, although the guarantees for social leadership within a context of violence remain, in many cases, in the imagination.

[i] Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia, is divided into 20 localities. Each one groups a different number of neighborhoods.

First publication, July 7, 2020 and, second publication, August 13, 2020, © All rights reserved